Friction, speed and surprise: What sets Wimbledon’s grass courts apart from clay, hard courts

Understanding how different tennis court surfaces like grass and clay play requires knowledge of the physics behind them.

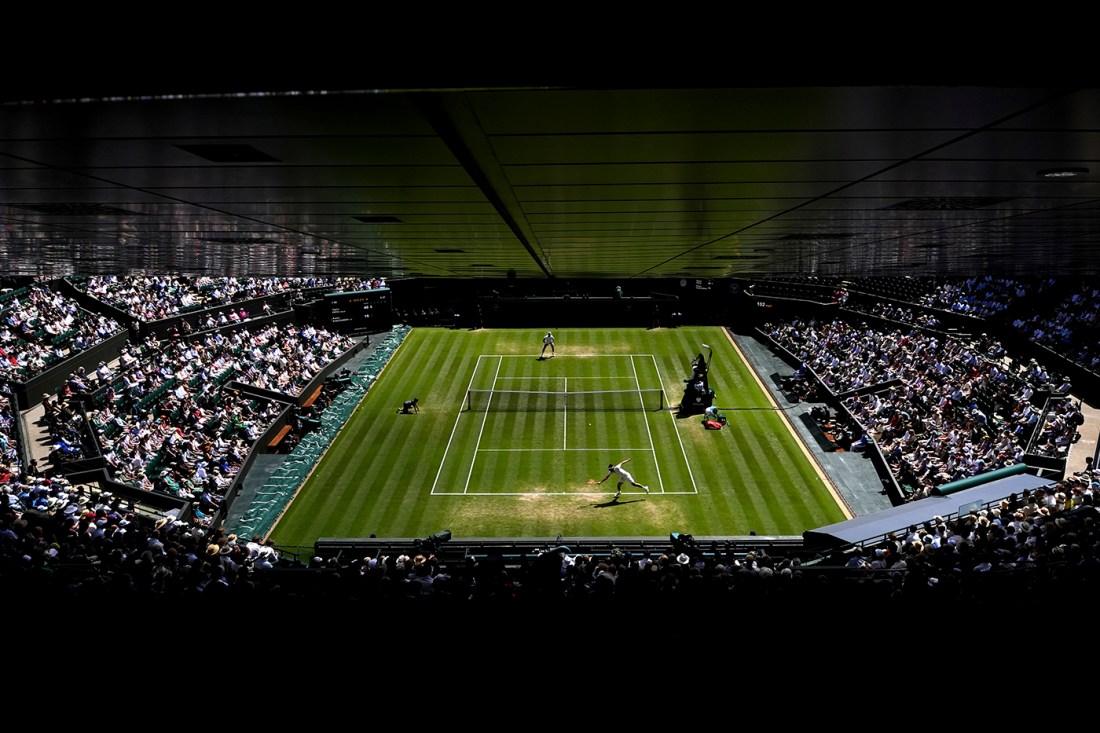

The grass tennis courts of Wimbledon are among the most recognizable in the world.

But despite its fame, grass is one of the rarest surfaces on which tennis is played today; many tennis fans and players may never set foot on its lush turf during their lifetimes.

How does the iconic Centre Court lawn compare to the gritty red clay courts of the French Open, where last year’s Summer Olympics took place? Understanding how different tennis court surfaces like grass and clay play requires knowledge of the physics behind them.

Wimbledon’s grass courts create fast, low bounces

There are fundamental differences in the physics of grass and clay courts, says Arun Bansil, a university distinguished professor of physics at Northeastern University.

“Grass courts have lower friction and absorb more energy during the bounce,” Bansil says. “As a result, the ball bounces low due to loss of vertical speed, but bounces fast due to lower friction and smaller loss of horizontal speed.”

It’s that zippy, low-bouncing quality that defines gameplay on a grass court. For amateurs and professionals alike, the surface is among the trickiest on which to find your footing — requiring that you keep your body low to meet the ball.

“Surfaces matter for three reasons: the degree to which the ball loses speed on the bounce, the height of bounce and the level of traction players have for moving,” says Gill Gross, a tennis commentator and analyst.

“Grass is traditionally the most slick surface because there’s less friction when the ball hits the court, and … because it’s a softer surface it ends up bouncing lower,” Gross says. “It is also the most slippery surface, which makes it difficult for players to cover the court effectively.”

How friction and spin change across surfaces

Clay courts, on the other hand, have more surface friction, resulting in more “grip” on the ball, a slower pace of shot but a much higher bounce.

On a clay court, the ball seems to sit on the court for a split second longer: that’s the friction at play, which slows the shot and converts the ball’s spin into vertical lift.

Grass courts are also more sensitive to temperature and humidity and other external effects, which is why the ball behaves less predictably, Bansil notes. In drier temperatures, the soil beneath the grass is firmer, causing the ball to zip through the court more.

In slicker conditions, the ball might play even lower to the ground, as the moisture absorbs more pace. Slick grass can also pose problems for a player’s movement, particularly during the first week of Wimbledon when the turf is lush and less worn down.

“Grass courts perhaps provide a more interesting play for these reasons because the spectators are likely to experience more unexpected turns in the match than on, say, hard courts,” Bansil says.

Editor’s Picks

Early upsets of 2025 highlight grass court volatility

Unexpected is perhaps a good way to describe the first week of the 2025 Wimbledon Championships, which saw dozens of top seeds fall in the early rounds. Every year the tournament begins with 64 seeds across the men’s and women’s singles draw. Positions in the draw are determined at random but plotted in such a way as to prevent top-ranked players from playing each other too early in the tournament.

By the third round, only 27 of the seeds had survived in both draws, the fewest since the format was adopted in 2001, according to The Athletic.

As the tournament progresses and the turf is worn down, the courts become less treacherous, but potentially more unpredictable on the bounce as players have to navigate areas of the court — usually near the baseline — where the grass is worn bare. After a week or so of competition, the courts tend to develop a large, uneven patch of dirt that can generate awkward bounces. (This is especially true of Centre Court and No. 1 Court.)

Lawn tennis and its evolution

Once referred to as “lawn tennis,” grass court competition has shaped the way players develop and execute their games — not just on grass, but on other surfaces as well. At the turn of the 19th century, early competition at three majors — Wimbledon, the U.S. Open and the Australian Open — took place on grass courts. Traditionally, players adopted a serve-and-volley style game suited to the quick pace of grass court competition.

Such a style usually involves an effective first serve, strong volley technique and the deployment of a slice backhand to keep the ball low to the ground. Those who best typified this now-dated style of tennis include past Wimbledon champions: John McEnroe, Stefan Edberg, Boris Becker, Pete Sampras and Roger Federer.

Gross says that grass court tennis involves more sliced groundstrokes (to generate backspin), and more slice serves (to generate sidespin).

By and large, grass courts rewards adept movers (short choppy steps are important for deceleration, Gross notes) and offensive-minded tennis.

“Offensive play is rewarded on grass, since the ball moves through quickly and it is difficult to cover court,” he says. “The logical adjustment for players is to play more attacking tennis whenever possible.”

Today, there are only a handful of tournaments — just seven, according to the Association of Tennis Professionals, of the more than 60 on the calendar — played on the evergreen surface, including the world’s oldest and most prestigious competition.

But Gross says there is a desire on the part of fans to see more grass court competition.

“The surface is visually appealing and offers some welcome novelty within this non-stop 11 month-long season,” he says.