How realistic is the nuclear threat in Netflix’s ‘A House of Dynamite’?

In Kathryn Bigelow’s new movie, a nuclear missile is headed for the U.S. But what can we really do to defend ourselves against a nuclear threat? This expert has a sobering answer.

For the characters in “A House of Dynamite,” an acclaimed new political thriller from Oscar winner Kathryn Bigelow, the end of the world is not hypothetical.

A nuclear missile is headed for the United States. Nobody knows who launched it, but the president and those in the White House Situation Room have 18 minutes to avoid nuclear annihilation. Bigelow’s return to the director’s chair after nearly 10 years, “A House of Dynamite” is both a high-intensity thriller and chilling reminder that the Nuclear Age is far from over. It also raises an uncomfortable question: What could the U.S. do if a nuclear missile were actually launched its way?

The answer is even more sobering.

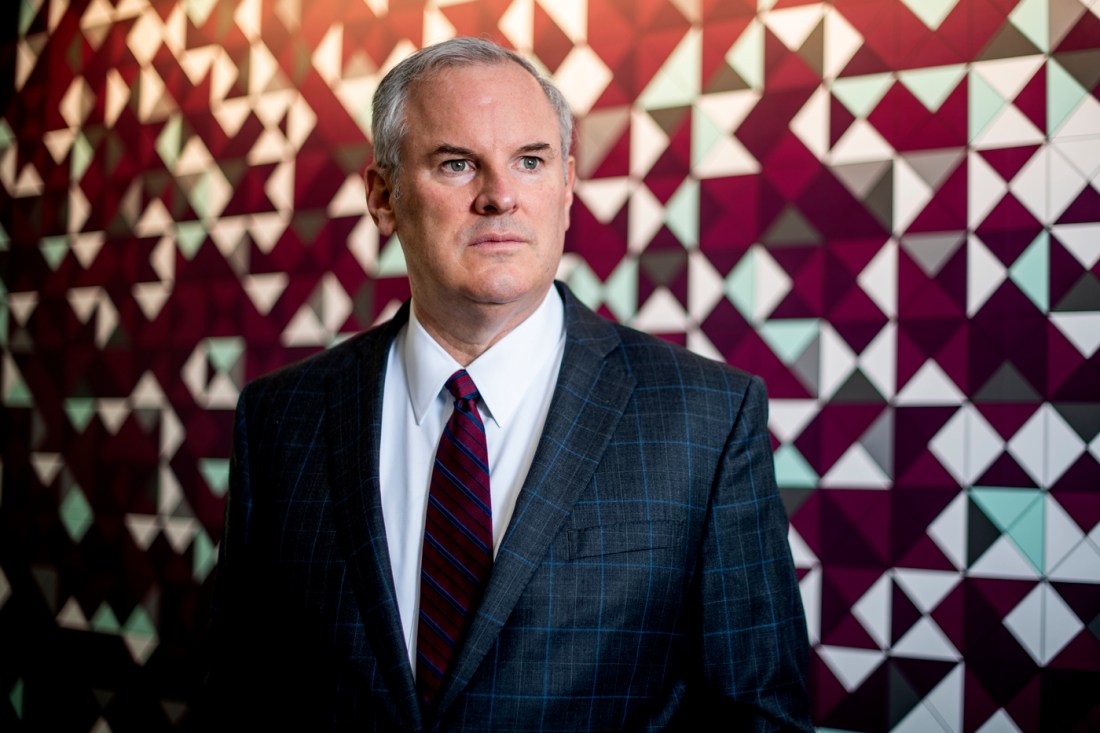

“The short answer is there is not much capability if we’re in a post-launch stage and the missile is incoming,” says Stephen Flynn, a professor of political science and founding director of the Global Resilience Institute at Northeastern University.

“The aspiration going back to the mid-1980s when Ronald Reagan pushed for the whole missile defense effort was that we would develop the capability to have a defensive means that, should a missile come our way, we’d be able to shoot it out of the sky,” adds Flynn, who recently chaired a committee for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine focused on nuclear terrorism risk. “Of course, Trump’s more recent push for the Golden Dome is animated by the same approach. But both the Strategic Defense Initiative and the Golden Dome remain aspirational right now.”

If the threat posed by nuclear weapons is so existential, why hasn’t the U.S. developed more defensive options? It’s partially a technological challenge, Flynn explains.

When one character in “A House of Dynamite” compares shooting a nuclear missile out of the air to trying to hit a bullet with a bullet, they’re not wrong. According to Flynn, the ideal goal is to eliminate a missile at launch because once it’s moving at top speed and hitting the edge of low Earth orbit, they are nearly impossible to hit. Early solutions to this problem in the Reagan era proved just as problematic as the missile itself.

“Just the physics of it was really daunting,” Flynn says. “The ability to create the means to actually hit the weapon –– the laser you’d need to zap the weapon in flight –– required a nuclear event. You had to actually create nuclear energy by setting off a nuclear device in space in order to create the laser that would shoot it out of the sky.”

Missile defense systems like those deployed in Israel and Ukraine are effective but highly localized. For a much larger country like the U.S., deploying a system like that scale would prove challenging, he explains.

“There still is a sense that there’s not going to be a quick fix,” Flynn says. In many scientific quarters, it’s an aspiration that … certainly not going to happen in the short term or medium term.”

Editor’s Picks

Between “A House of Dynamite,” “Oppenheimer” and James Cameron’s upcoming adaptation of “Ghosts of Hiroshima,” nuclear weapons are back in the spotlight, at least for Hollywood. Flynn says it comes at the right time.

During the Cold War, the specter of nuclear war was constant. It led to sobering conversations, Flynn recalls of his time serving in the White House military office under President George H.W. Bush. Intelligence at the time estimated that a nuclear strike on the U.S. would likely kill three-quarters of the U.S. population.

“It really focused the mind –– and bipartisan focused the mind –– around, ‘We’ve really got to stay on top of this threat,’” Flynn says. “That went away when the Cold War went away.”

Now, there is a troubling combination of a lack of public awareness around nuclear threats and a greater number of nuclear threats, between the U.S., Russia, China and, now, various non-state actors.

“The bottom line is we’re almost certainly in a world where we have more, not fewer [nuclear weapons] and we’re much more destabilized,” Flynn says.

Flynn hopes a movie like “A House of Dynamite” can raise some awareness about the threat still posed by nuclear weapons. However, he hopes it also sparks a conversation about what can actually be done to respond to this threat. If the U.S. isn’t going to build active defensive measures anytime soon –– and nonproliferation has been thrown to the wayside –– Flynn says the only option is to improve civil defense measures.

That means educating the American public about what the real threats are and how to respond in the aftermath of an attack.

“These are basic, almost first aid-like truths that we need to, in this age, make sure people have some understanding of,” Flynn says.

The likelihood of a single nuclear device deployed not by another country but by a non-state actor is the most probable risk, he explains. In that case, there are basic tips the public should know about sheltering in place –– “go low and hide,” he says –– rather than trying to “get in your car and … run for dodge.”

“The value of a movie like this … is that it raises awareness,” Flynn says. “If you give people both awareness of a threat but empower them with how to deal with that threat, you reduce that panic-like response and you’re in a better place than you otherwise might be.”