New Northeastern initiative prepares STEM educators for effective AI integration into high school

Funded by the National Science Foundation, the program equips educators with knowledge, tools and support to help students thrive in an AI-driven world.

As artificial intelligence transforms how people work and learn, Northeastern University has launched a new initiative to help STEM educators bring AI into high school classrooms.

This summer, Northeastern welcomed its first cohort of Massachusetts teachers and administrators to a professional development program focused on integrating AI in high school education.

Funded by the National Science Foundation, the program equips educators with knowledge, tools and support to help students thrive in an AI-driven world.

“When students have careers, they’re going to be using it in lots of different ways,” says Matt Costa, director of STEM disciplines at Revere Public Schools. “So, how can we thoughtfully build it up?”

But AI in education can be a polarizing topic, says Kathleen Bateman, program director for science at Boston Latin School.

“When we have these conversations in our schools and in our districts, everyone assumes there’s an agenda, that someone’s trying to either be pro-AI or anti-AI,” she says. “You can’t really take a minute to catch your breath and explore the tools.”

That’s why Bateman and Costa joined the Northeastern-led program. It aims to provide STEM educators with the skills and time to engage critically with AI tools — and with each other — on how best to implement them.

“This opportunity has allowed us to speak with people from all different sizes of schools and school districts and talk about how it would impact all levels of learners, students with learning differences, students where English is not their first language, and it’s just given us the time to breathe and … think critically about our own institutions,” Bateman says.

Bridging policy gaps in AI education

Northeastern’s three-year initiative aims to build a professional learning community for STEM teachers across Massachusetts. The goal is to create a network where educators can exchange ideas, support one another and advocate for equitable and responsible integration of artificial intelligence in the classroom.

Each summer, about 10 teachers from across the state will be selected to participate. The inaugural cohort, which completed its training in July, included 12 educators. Their experience began with modules on the history and fundamentals of AI, followed by an intensive week of training and a year-long series of monthly sessions with ongoing content support.

“The teachers’ attitude changed 180 degrees at the end of this summer’s institute,” says Ibrahim Zeid, professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at Northeastern.

Zeid applied for the program’s NSF funding and led training sessions for the teachers.

“They became very knowledgeable in AI and prompt engineering, and available AI tools,” he says. “The AI for educators program enables transition to an AI-based pedagogy. K-12 STEM education must keep pace with industry where major companies are racing to develop and use generative AI tools.”

Despite growing interest in AI, many educators face uncertainty about its use in the classroom due to inconsistent policies. Claire Duggan, executive director of Northeastern’s Center for STEM Education, says the current policy landscape is fragmented.

Editor’s Picks

“There’s wide variations across districts in Massachusetts and all across the country in terms of having policies and not having policies,” Duggan says. “There may be some districts that may have decided [to use AI], but individual schools have the freedom to decide if they’re not ready to use [it] and block [it].”

Educators seek guidance — and balance

Currently, many teachers and students are exploring AI independently, often without formal support.

“I have been using AI for a while,” says Pakamas Tongcharoensirikul, a chemistry teacher at Quincy High School. “Still, my students know more about AI than me.”

Without clear policies, teachers express concerns about plagiarism, ethical use and which tools are appropriate for students. Districts also vary widely in their restrictions.

Federal law, such as the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act, limits access to some tools for younger students.

“Being part of a workshop like this informs us, so that we can bring that information back to our districts and hopefully convince administrators, superintendents about the power of AI and the fact that students should have access to it as long as they’re using it in a meaningful and appropriate way,” says Mark Casto, a chemistry teacher and science department head at Amesbury High School.

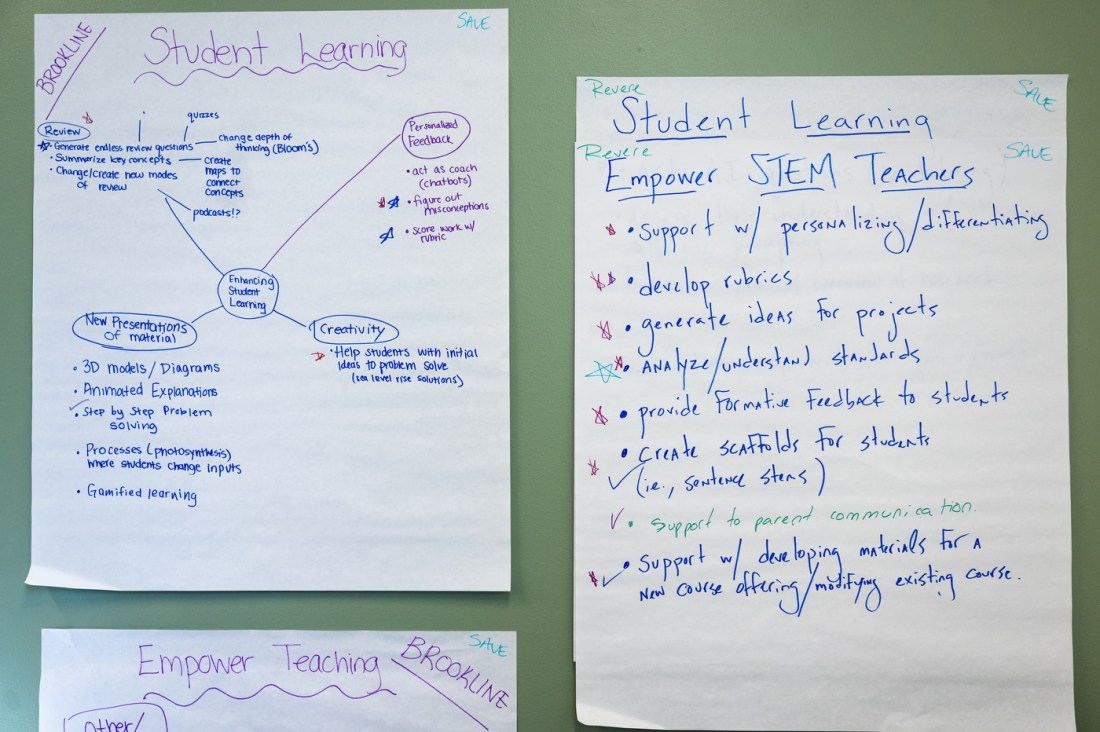

During the training, educators evaluated AI tools relevant to STEM subjects, practiced prompt strategies and developed lesson plans that align with Massachusetts Science, Technology/Engineering Curriculum Frameworks. They also discussed how AI can support students with diverse learning needs.

“This week has really helped us understand that there are advantages and disadvantages for students,” Bateman says.

Some teachers, like Bateman, believe AI may be best suited for older students who are ready to use it responsibly. Others worry about how overuse may undermine core learning experiences.

AI isn’t meant to replace teachers, participants emphasized, but to support them.

“If used correctly, AI has the power to make us more efficient teachers by taking away some of the tasks that we have to perform as educators, and with that additional time, we can be in front of students more and engage students more,” Casto says.

Heather Giblin, a biology and marine science teacher at Brookline High School, says she now better understands the difference between AI-informed teaching — where educators use AI to enhance their own lesson planning — and AI-powered teaching, where the technology directly supports student learning.

Human connection still comes first

While many AI tools offer promise, educators say the value of face-to-face teaching remains irreplaceable.

“It’s less about the content than it is about the personality,” says Adam Sasso, who teaches electives like video production and robotics at Cohasset High School. “I don’t think that AI on a screen is ever going to replace face-to-face, eye-to-eye contact and the soul, and the love that teachers give to their kids.”

Teachers also raised concerns about digital equity. Not all students — or districts — have the same access to AI platforms, which may be limited by cost or availability.

“There are some free versions of things, but will that last?” says Edward Savage, a biology teacher at Cohasset High School.

That’s why teachers play a crucial role in bridging gaps in opportunity, says Nahuel Acosta Burroso, a physics teacher from Revere High School.

“If some [students] are finding AI useful, then we should get everybody to find the same useful way,” he says.

Costa also cautions against offloading too much instructional work to AI.

“There’s work that we can offload to AI to make our jobs easier, but are we offloading the right work? Because there’s work that we can do better and we should be doing,” he says.

He believes reviewing student work directly allows educators to track progress, give feedback and strengthen relationships.

Another concern is the potential impact on students’ social and communication skills.

“I don’t want them staring at screens and just asking all their questions to the computer,” says Melissa Nixon, a physics teacher at Brookline High School. “I want them to play around and get messy, but also know how to talk to each other.”